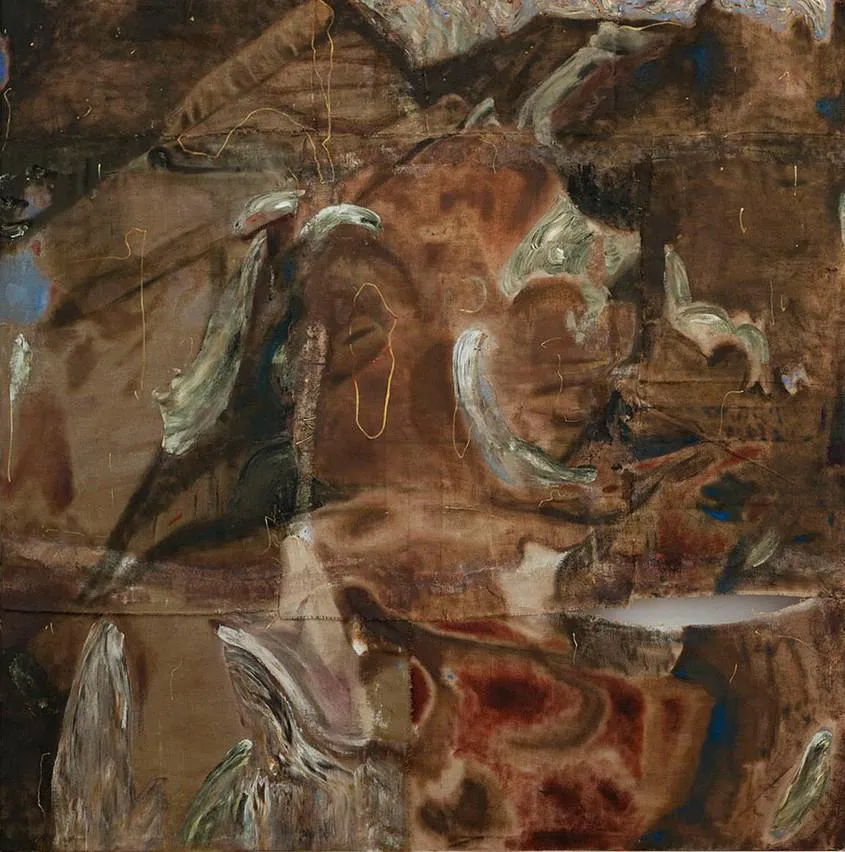

Æmen Ededéen: The Work’s Pathos should Come from Its Worn-out-ness III

J: I can clearly perceive the profound importance of your family in your life. I’m curious to inquire whether family members have exerted any influence on your career development and artistic creations. Furthermore, we kindly invite you to share the story behind the creation of The Epistle of One Arriving from Among the Many Departed, which is currently on display in this exhibition.

E: I’ve often discussed the loss of my youngest brother when I was six, which was a foundational event rippling out into all areas of my life from then to now. What I’ve often left out of the story was the strange inner abundance which accompanied that loss. When my brother died, I escaped into worlds of my own making, drawing my own comic books and telling my own stories from a very early age. Because I believed in Heaven, I imagined a fantastical version of Danny capable of doing anything, being anything, and I attached my own unexpressed feelings that basic image. A kind of wild twin was embedded in my inner life. I even went through a period shortly after Danny’s death in which I began saying everything twice, first in my normal voice, then in a whisper.

The painting The Epistle of One Arriving from among the Many Departed was made from sonogram images of our daughter while Maja was pregnant. It was one in a series of eight paintings I called the “Sonogram Series.” When she was born, Maja had an emergency c-section. That morning, our cat was scratching a closet door and when I opened it a small finch flew out, through our kitchen, and into the office. Our cat seized and killed it in a matter of seconds. All of this occurred while Maja was having contractions.

The emergency birth was hard on Maja, and, because it was during Covid, I found myself out in the hospital hallway with Mila on a warmer during her first hour of life. This hour was profoundly important. I made a massive painting called “The Hour” which came out of this experience. I could see that she could see me (infants can’t see far) and that a bond was immediately forming as her tiny hand gripped my finger. It was as if I could see all of existence, as cheesy at that sounds, in her face. All that morning and afterward I could feel the presence of my brother nearby. It was as if he formed a passage through which we could pass, and the bird and our cat were like signs of the danger all around this passage. From the time of her birth until now, I’ve imagined him aging and growing in tandem with her. I can’t explain it.

The kinds of things I’m discussing here are those that Maja and I discuss in our private life together every day. They’re things one can’t discuss with most people. I believe we’re both engaged in the same consideration at our different and varied scales and positions. The questions and insights, the way we come to the material, all of that is unique to each of us, but we are both circling around the same source. This 12-year conversation between us has affected everything about my work. I consider myself remarkably fortunate that this is so. She is, after all, one of the best living painters we have.

Edit by Sai, Veronica